The summer has presented me with challenges–one after another–and some, which I had hoped to avoid. Having an ill parent with few options for an acceptable living environment is something I would wish on no one. It is my worst nightmare, and to avoid feeling physically sick over the situation, I try to find small moments each day to see beauty in the world, and to appreciate the wonder of others.

The summer has presented me with challenges–one after another–and some, which I had hoped to avoid. Having an ill parent with few options for an acceptable living environment is something I would wish on no one. It is my worst nightmare, and to avoid feeling physically sick over the situation, I try to find small moments each day to see beauty in the world, and to appreciate the wonder of others.

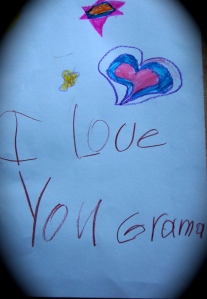

My five-year-old granddaughter is a blessing, particularly now when my family faces some of the hardest decisions of our lives. Ava makes me stop, forget about the barrage of depressing phone calls, and take a moment to live life in an idealist way.

My five-year-old granddaughter is a blessing, particularly now when my family faces some of the hardest decisions of our lives. Ava makes me stop, forget about the barrage of depressing phone calls, and take a moment to live life in an idealist way.

In our large front yard, I am free—even for just thirty minutes—to laugh, chase Ava through the grass with our dog Merlin, and wonder at the miracles of the tiniest of creatures. We remain like statues when the hummingbirds zoom above us. We watch the bees on my Echinacea, revel in the sight of a butterfly, and kneel on the cool ground to peer into a daylily to marvel at fascinating insects, which appear to be from outer space. They are smaller than ants in actuality.

In our large front yard, I am free—even for just thirty minutes—to laugh, chase Ava through the grass with our dog Merlin, and wonder at the miracles of the tiniest of creatures. We remain like statues when the hummingbirds zoom above us. We watch the bees on my Echinacea, revel in the sight of a butterfly, and kneel on the cool ground to peer into a daylily to marvel at fascinating insects, which appear to be from outer space. They are smaller than ants in actuality.

A frog leaps before us and Ava is off, chasing the tiny amphibian, catching it . . . losing it . . . and then catching again. Her hands tightly clasped, she tells me, “Grandma, the frog is berry thirsty. And he needs a home to live in.”

A frog leaps before us and Ava is off, chasing the tiny amphibian, catching it . . . losing it . . . and then catching again. Her hands tightly clasped, she tells me, “Grandma, the frog is berry thirsty. And he needs a home to live in.”

Just like my father, I think. Why is it that we cannot find suitable housing for the elderly where they can be respected and loved and treated with dignity? I brush the thought aside and head indoors for a small bowl. Ava follows, and my eyes stay fixed on what is contained within her grasp. “Don’t let that frog loose in the house,” I say. The cats would have a field day.

I fill a small, short container with water, and we go back outside. With great care, Ava places the frog in the bowl. It swims happily, and then leaps for freedom.

I fill a small, short container with water, and we go back outside. With great care, Ava places the frog in the bowl. It swims happily, and then leaps for freedom.

“Uh-oh,” she says, leaning over to trap the frog once again. “I think he wants some food.” With great precision, she keeps the creature safe, while using two fingers to add clumps of grass and a smattering of dirt. The frog back in the bowl, it swims the best it can among its new challenges, and then escapes.

“Uh-oh, says Ava, clamoring to catch it. The frog is faster than she is, and soon is nowhere in visible sight. “Oh, no, I didn’t find it a friend!”

“We’ll find something else.” And we do. On the porch, we discover an injured moth. Carefully, Ava scoots it onto the palm of her hand. “Oh, Grandma, he is so sweet. Can you fix him, please?”

“We’ll find something else.” And we do. On the porch, we discover an injured moth. Carefully, Ava scoots it onto the palm of her hand. “Oh, Grandma, he is so sweet. Can you fix him, please?”

Can I heal my father? No, and I know I can’t fix the moth’s wings, but I don’t say this to her. Instead, I follow her around the yard.

“We have to find the moth a place to rest, that’s nice. So he can get better and fly away,” Ava says. “He wants to go back to his family.” No matter how large or small a creature is, Ava is always concerned that they have a family to be with, or at least, friends.

Until our new porch is completed, all of my garden statues are under our red maple tree, and this is where she heads. After she walks around the tree, twice, Ava settles on a cherub lying on its back.

Until our new porch is completed, all of my garden statues are under our red maple tree, and this is where she heads. After she walks around the tree, twice, Ava settles on a cherub lying on its back.

“Perfect,” she says, “This is just perfect.” She hopes the moth will survive, despite its apparent odds, and in the morning, when she checks to see if the moth is still there, she announces happily that it has flown away. The family of moths is reunited. (I find it later—lifeless and snuggled in the crease of the cherub’s wings—in a place she did look and I do not tell her.) I want her to believe the moth lived, as I wish to cling to the belief that the situation for my father will improve. I am not prepared to let go of hope. Some days, all we have is hope.

Satisfied that the moth is settled in for the night, Ava resumes her frog search, and with unbelievable luck, she finds it, or its sibling, or a relative of some sort, I guess. Her new mission is to find the frog a friend. The sun begins to set, which does not deter Ava in her quest. She carries the frog in her clasped hands, while I follow and dig where directed. I check under leaves, around flowerpots, between rocks, and anywhere else, she believes the frogs are hiding from her. In the meantime, twilight falls upon us.

Satisfied that the moth is settled in for the night, Ava resumes her frog search, and with unbelievable luck, she finds it, or its sibling, or a relative of some sort, I guess. Her new mission is to find the frog a friend. The sun begins to set, which does not deter Ava in her quest. She carries the frog in her clasped hands, while I follow and dig where directed. I check under leaves, around flowerpots, between rocks, and anywhere else, she believes the frogs are hiding from her. In the meantime, twilight falls upon us.

“Ava, you have to find somewhere to put the frog, and not in the house.”

“I know, I know, Grandma.”

Clearly, this quest will soon require flashlights.

Suddenly, Ava remembers one garden statue not under the maple tree. “Come on, everybody!” she says. Merlin and I follow her to the backyard.

“Look, everybody, this is just perfect.” Leaning over, Ava places the frog in the middle of a statue of two frogs. “Perfect! Now, he has a family!”

Thankfully, the frog seems content; he stays exactly where Ava places him, until she runs off to chase a fleeting dragonfly.

Thankfully, the frog seems content; he stays exactly where Ava places him, until she runs off to chase a fleeting dragonfly.

“Is he still with his family?” she calls back to me.

“Yes.” Well, for the moment he is, before leaping through the white fencing to explore a world free of curious little girls, intent on being matchmakers or reuniting long-lost family members.

We chase fireflies until I hear the phone ring. While receiving an update on my father, Ava finds other lives to run. Once the conversation with my sister ends, I learn that Ava has played matchmaker with our cat Terrapin. Terrapin is to marry Ava’s Steiff black leopard and have two babies, instantaneously. The wedding ceremony is performed without complications. To my surprise, Terrapin does not flee the makeshift alter, and she even poses for formal photos without a single complaint. Well, maybe a glare or two. Once Ava knows that the babies are being tolerated by the new bride and groom, we settle down to read books . . . and books. I am thankful for the distraction.

We chase fireflies until I hear the phone ring. While receiving an update on my father, Ava finds other lives to run. Once the conversation with my sister ends, I learn that Ava has played matchmaker with our cat Terrapin. Terrapin is to marry Ava’s Steiff black leopard and have two babies, instantaneously. The wedding ceremony is performed without complications. To my surprise, Terrapin does not flee the makeshift alter, and she even poses for formal photos without a single complaint. Well, maybe a glare or two. Once Ava knows that the babies are being tolerated by the new bride and groom, we settle down to read books . . . and books. I am thankful for the distraction.

Now, two days later, I sit by the window, awaiting the return of the Baltimore orioles. I review the pictures I took with Ava, and the photos I was fortunate to have the opportunity to shoot the day before, on my way to work: a Great Egret and a Blue Heron. Both phones (cell and landline) are charged and by my side. I have already taken six calls this morning regarding my father, the first at 4 am, at a time when I was doing one of the following: ripping off covers . . . whipping them back, staring at the clock . . . trying to not look at the clock, fluffing my pillow . . . punching my pillow, opening the window . . . closing the window, petting a cat . . . shoving a cat off of my chest.

Now, two days later, I sit by the window, awaiting the return of the Baltimore orioles. I review the pictures I took with Ava, and the photos I was fortunate to have the opportunity to shoot the day before, on my way to work: a Great Egret and a Blue Heron. Both phones (cell and landline) are charged and by my side. I have already taken six calls this morning regarding my father, the first at 4 am, at a time when I was doing one of the following: ripping off covers . . . whipping them back, staring at the clock . . . trying to not look at the clock, fluffing my pillow . . . punching my pillow, opening the window . . . closing the window, petting a cat . . . shoving a cat off of my chest.

I cannot sleep. I cannot eat. I cannot write. And with the beginning of each new day comes the knowledge that my father will be calling, at any point, to ask about my writing.

Through his pain, my father continues to check the progress of my submissions; to remind me he is running out of time. I am losing this race to find success before his last breath, but I will not give up, even knowing I cannot fix what I want to fix, need to fix.

Through his pain, my father continues to check the progress of my submissions; to remind me he is running out of time. I am losing this race to find success before his last breath, but I will not give up, even knowing I cannot fix what I want to fix, need to fix.

I will remember the promise I made to my father and to myself. Whether it is through my photography, my interactions with my granddaughter, or another creative outlet, I will find the way back to my words.

In the past, my return to inspiration has started as a low hum, which quivers like a hummingbird’s wings, until I reach out to snatch it. Other times, lightning hits, catching me off-guard. Whichever way the relentless desire to create returns, I am ready. My heart is open, and until that moment, my inspiration comes from the hawk that soars in the sky above our house each night. Drifting on the wind, it flies free and without worries. I watch and I dream . . .

I dream of dancing. I dream of dancing across the page with words and images. I dream of dancing to places only I can find, kept safely, for now, within me.

I dream of dancing. I dream of dancing across the page with words and images. I dream of dancing to places only I can find, kept safely, for now, within me.

This is who I am.

This is what I know.

I am my father’s daughter.

When I struggle with putting words

When I struggle with putting words I, too, want to silently dive deep,

I, too, want to silently dive deep, And then I find myself in awe of tadpoles,

And then I find myself in awe of tadpoles, So I leave my critical self outside

So I leave my critical self outside